Joani Etskovitz joined CMC as an Assistant Professor of Literature this fall, but only after giving The Claremont Colleges libraries her stamp of approval.

“First thing, the day before my interview, after the plane touched down, I visited all the libraries. They were fabulous,” Etskovitz said.

It’s no wonder, as the Philadelphia native grew up immersed in the city’s rich collection of libraries and museums. As a Princeton undergraduate, she further solidified her career aspirations through meaningful experiences in two of the greats: Princeton’s Cotsen Children’s Library, which houses one of the world’s most significant collections of rare children’s books, and the Library of Congress, where she interned in the Young Readers Center.

In these world-class spaces, and later in the Bodleian and Houghton Libraries, Etskovitz delighted in designing outreach programs, leading educational events, and curating exhibits—all centered on British novels and children’s books. Becoming a professor of literature, she realized, would synthesize these passions with her affinity for academia.

“This was the role that would allow me to do everything I wanted to do. It feels cliché when I say it, but this is the dream,” said Etskovitz, who earned two master’s degrees at the University of Oxford and her Ph.D. at Harvard.

Etskovitz has been “full of wonder” since joining CMC, particularly energized by the small class sizes: “It’s a great fit for me because of the level of engagement I want to have in the classroom.”

A passionate scholar, Etskovitz’s current research focuses on the origins, popularization, and impact of the 18th- and 19th-century “feminist adventure novel,” a genre of fiction that propelled its heroines beyond the marriage plot, into exploration and education.

Etskovitz engages today’s student in timeless questions about identity, rights, and societal expectations in “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists?”, a course she developed based on novelist George Eliot’s 1856 satirical essay of the same name … but without the question mark. Eliot’s searing essay calls for more serious consideration of women’s fiction writing (the very impetus for Mary Ann Evans’ adoption of the pen name George Eliot) and lambastes any association between the worth and rights of women and the content of the period’s novel genre.

“Why were readers using the novel genre to assess whether women deserved education and places in print? That’s a troubling, historically complicated connection,” Etskovitz remarked.

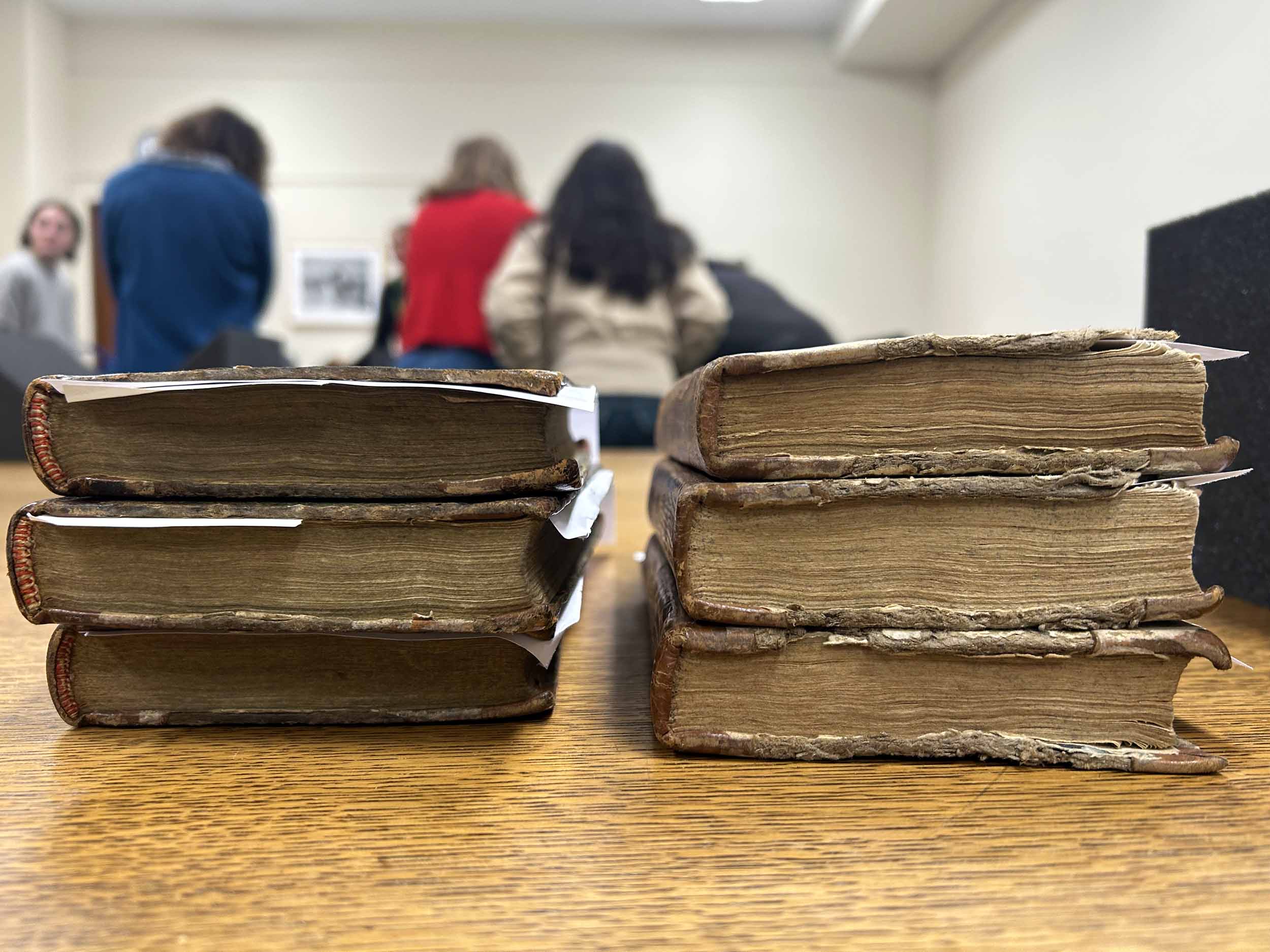

Students taking Etskovitz’s “Silly Novels?” course, along with those in her “First-year Writing Seminar: The Young Adult Novel,” recently expanded their in-class learning through an excursion to The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in Pasadena.

With the world-class libraries of her undergraduate years so influential, Etskovitz sought to introduce students to The Huntington as a similar resource. A true testament to the power of the liberal arts, it was also an excellent way to expose students to the broader historical context of the books they’re reading.

“They should have the chance to see the texts that are underpinning what they’re studying,” said Etskovitz.

Taking in the fragile first editions and various early manuscripts pulled from The Huntington’s Special Collections (Ahmanson) Reading Room, Alahna Gainer ’28 found the experience a valuable complement to her coursework.

“This adds importance to what we’re reading,” Gainer said. “It’s easy to view an old book— like this just exists—and not think about it beyond the bounds of the page. But when it’s put in a historical context, it results in a deeper understanding.”

Drawing a fascinating parallel, Etskovitz noted that because of their social media immersion, students were well-prepared to engage with the antiquated materials—criticism, correspondence, even advertisements—that had such influence on the authors they’re reading.

“The Huntington texts showed my students historical versions of the kinds of conversations and impressions they encounter every day that shape their own stories, their own narratives,” Etskovitz said.

The cross-century similarity prompted Maya Chastang ’28, a student in the “Silly Novels?” course, to reflect on her own habits.

“In the novels we’re studying, many of the women read books that influence how they carry out their lives, or how they expect their lives to play out. So, I’ve been thinking about how media and the information we consume affects our perspectives and influences how we conduct our own lives,” she said.

On the horizon for Etskovitz in the spring: Debuting another unique course, “Blaming Charlotte Brontë.” Among other topics, students will examine the emotional intensity with which readers engage with Brontë’s work, as well as how the author responded to her own childhood reading. Etskovitz will also teach “British Writers II,” featuring the ever-popular Jane Austen in recognition of the 250th anniversary of her birth on December 16, 1775—or in literary parlance, “Austen 250,” which is inspiring major celebrations and learning opportunities around the globe.

“This is a chance to reflect on the ways in which Austen is still shaping contemporary culture,” Etskovitz said. “It is remarkable that this author, who published for a short time in the ‘18-teens,’ continues to be such a force for enrollment in literature and history departments.”

Austen’s enduring influence underscores the premise that lies at the heart of Etskovitz’s work, whether in the classroom or in the archives:

“Literature has a role to play in our real lives. It can shape us. It can guide our futures.”